Let's Write about Scott and Zelda in France!

Were F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda ever happy?

Their love story still sizzles!

|

| F. Scott Fitzgerald was born in Saint Paul Minnesota in 1896. He and Zelda were married in New York City's Saint Patrick's Cathedral, in 1920. |

This essay was published in the France Today electronic magazine (Ezine). To be honest, although I realize how infamous (or famous- depending how the couple's biographers might frame their lives) are and remain to this day, I was unaware about how their lives together were tumultuous, to say the least. I suspect the experiences described in this article about when F. Scott and his wife Zelda were in France, might have been some of their (sort of) happiest years together.

Drawing on his own experiences, Fitzgerald wrote short stories in a room above the garage. While his characters took shape, he and Zelda were busy burning cash, heedless that their newly extravagant lifestyle might be more ruinous than they imagined. The endless partying (often with his buddy and neighbor, Ring Lardner, a sports columnist and satirical short story writer) also kept Scott from concentrating on his new novel.

Tipped off by writer Edith Wharton that the palm-shaded, sleepy town of Hyères was an enchanting place to settle down, the couple found it too staid and swarming with dreary British pensioners. Instead, they rented a charming white villa, further down the coast, on a tranquil pine-shaded hillside in Saint-Raphaël – “a little red town built close to the sea, with gay red-roofed houses and an air of repressed carnival about it”. It was here, at the Villa Marie, that Scott cloistered himself to work on Gatsby, while Zelda spent long, idle afternoons at the beach, where she met a young French aviator, Édouard Jozan. Her passionate but short-lived affair with Jozan (recounted in Zelda’s semi-autobiographical novel, Save me the Waltz) soon put a strain on their marriage. Blame it on the dazzling landscape: the Riviera is “a seductive place,” wrote Zelda, “where the blare of the beaten blue and those white palaces shimmering under the heat accentuates hings”.

Zelda was dubbed by her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald as "the first American flapper". She and Scott became emblems of the Jazz Age, for which they are still celebrated.

Everyone gravitated towards the Murphys, stylish, charismatic trendsetters who attracted a charmed circle of friends that included the likes of Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, John Dos Passos, Rudolf Valentino, Fernand Léger, Serge Diaghilev and Pablo and Olga Picasso. They hosted elaborate picnics on the powdery sand of the then-deserted La Garoupe beach to the tune of Gerald’s latest jazz ballads on a portable phonograph, slathered themselves with cocoa butter, sunbathed and swam in the turquoise shallows (although allegedly, fair-skinned Scott preferred to lie in the shade, nursing a bottle of gin). Zelda, later remembered by the Murphy’s daughter, Honoria, as “blonde and soft and tanned by the sun”, was strikingly beautiful and always had a peony in her hair or pinned to her dress.

That summer, the Murphys set up headquarters in the empty pink seaside Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc – now one of the most iconic glitzy hotels on the Riviera – convincing the owner, Antoine Sella, to keep it open for them while their new home, the Villa America, was being built nearby. While Gerald entertained his friends with ritual cocktails (ingredients called for “the juice of a few flowers”), his guests Scott and Zelda would often liven up evenings with alcohol-fuelled antics that included diving off 11m-high rocks into a dark sea, or inciting guests to skinny dip in the pool. On another, more sobering occasion, Zelda swallowed a dangerous quantity of sleeping pills and walked around the hotel grounds all night.

In summer 1926, in the wake The Great Gatsby’s roaring success, the Fitzgeralds rented the Villa Saint-Louis in Juan-les-Pins to be close to the Murphys. It was “a big house on the shore with a private beach near the casino”, where Scott would work on the first chapters of Tender is the Night.

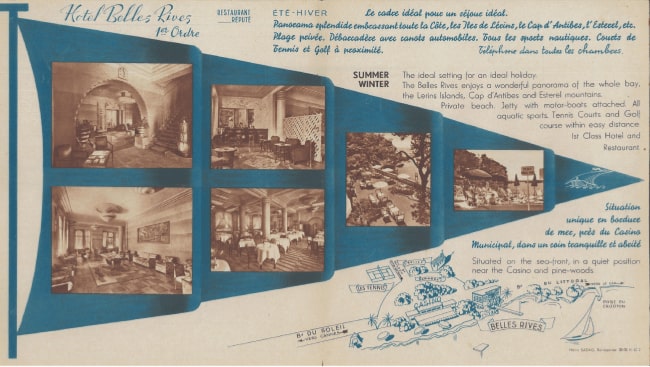

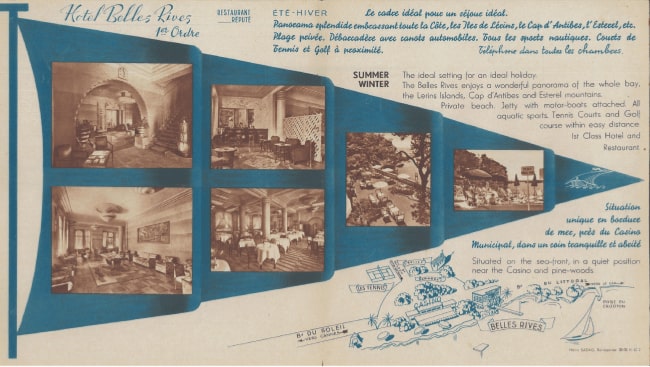

A vintage postcard of the Belles Rives hotel

Three years later, the villa was sold and transformed into a family-owned Art Deco mini-palace, Hôtel Belles Rives, whose 1920s décor has been meticulously preserved by the current owner, Marianne Estène-Chauvin. “Out of all the anecdotes passed down from generation to generation, my favourite is when Scott lured a local jazz band inside the villa and then locked them in a bedroom upstairs, and forced them to play dance music all night,” she says. Today, the hotel’s Fitzgerald Bar conjures up the Jazz Age; you’d almost expect to see Scott, hunched over a gin fizz, puffing on his Chesterfields, making notes.

Needing distraction, the Fitzgeralds would often set out in their little blue Renault along the red rock coastal road to the Cap d’Antibes, where their American friends, Sara and Gerald Murphy were staying.

Gerald, heir to the Mark Cross luxury leather goods company and a visionary painter, and Sara, a mid-western beauty who was believed to have been Picasso’s secret muse, may be best known as Fitzgerald’s initial models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night.

Gerald, heir to the Mark Cross luxury leather goods company and a visionary painter, and Sara, a mid-western beauty who was believed to have been Picasso’s secret muse, may be best known as Fitzgerald’s initial models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night.

|

| F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) with Zelda (Sayre) Fitzgerald (1900-1948) |

Zelda was dubbed by her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald as "the first American flapper". She and Scott became emblems of the Jazz Age, for which they are still celebrated.

Everyone gravitated towards the Murphys, stylish, charismatic trendsetters who attracted a charmed circle of friends that included the likes of Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, John Dos Passos, Rudolf Valentino, Fernand Léger, Serge Diaghilev and Pablo and Olga Picasso. They hosted elaborate picnics on the powdery sand of the then-deserted La Garoupe beach to the tune of Gerald’s latest jazz ballads on a portable phonograph, slathered themselves with cocoa butter, sunbathed and swam in the turquoise shallows (although allegedly, fair-skinned Scott preferred to lie in the shade, nursing a bottle of gin). Zelda, later remembered by the Murphy’s daughter, Honoria, as “blonde and soft and tanned by the sun”, was strikingly beautiful and always had a peony in her hair or pinned to her dress.

That summer, the Murphys set up headquarters in the empty pink seaside Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc – now one of the most iconic glitzy hotels on the Riviera – convincing the owner, Antoine Sella, to keep it open for them while their new home, the Villa America, was being built nearby. While Gerald entertained his friends with ritual cocktails (ingredients called for “the juice of a few flowers”), his guests Scott and Zelda would often liven up evenings with alcohol-fuelled antics that included diving off 11m-high rocks into a dark sea, or inciting guests to skinny dip in the pool. On another, more sobering occasion, Zelda swallowed a dangerous quantity of sleeping pills and walked around the hotel grounds all night.

In summer 1926, in the wake The Great Gatsby’s roaring success, the Fitzgeralds rented the Villa Saint-Louis in Juan-les-Pins to be close to the Murphys. It was “a big house on the shore with a private beach near the casino”, where Scott would work on the first chapters of Tender is the Night.

A vintage postcard of the Belles Rives hotel

Three years later, the villa was sold and transformed into a family-owned Art Deco mini-palace, Hôtel Belles Rives, whose 1920s décor has been meticulously preserved by the current owner, Marianne Estène-Chauvin. “Out of all the anecdotes passed down from generation to generation, my favourite is when Scott lured a local jazz band inside the villa and then locked them in a bedroom upstairs, and forced them to play dance music all night,” she says. Today, the hotel’s Fitzgerald Bar conjures up the Jazz Age; you’d almost expect to see Scott, hunched over a gin fizz, puffing on his Chesterfields, making notes.

For the Fitzgeralds – self-avowed “excitement eaters” – there was no better place for a glamorous jaunt than Monte Carlo. The couple would take the Grande Corniche, “through the twilight with the whole French Riviera twinkling below” and spend the evening at the casino. If Scott had forgotten his passport, he’d pretend to faint in front of the gambling room, hoping that they would somehow let him in. When it came to restaurants, fine cuisine was never a priority for Scott, who preferred club sandwiches and abhorred garlic. However, the artists’ haunt, La Colombe d’Or in Saint-Paul-de-Vence was the place to be seen, even then. One evening, Scott spotted Isadora Duncan at the next table and went to pay her court. Outraged, Zelda showed her jealousy by plunging down a flight of stone steps.

(??? OMG)

Don’t miss your chance to dine at La Colombe d’Or

Return to America: In 1929, the Fitzgeralds spent their last summer on the Riviera. When the Stock Market crashed in the autumn of that year, the gaiety was gone. Living in a villa in a less fashionable part of Cannes, the Fitzgeralds now avoided the Hôtel du Cap, a celebrity circus where silk-clad matrons used the pool “only for a short hangover dip”.

By this time, Zelda, who was doggedly working at becoming a ballerina, was showing signs of mental strain, and their cash was running low. Still, that didn’t stop the Fitzgeralds from exploring Nice, staying at the Hôtel Beau Rivage on the seafront, where “they were serving blue twilights at the cafés along the Promenade des Anglais for the price of a porto and we danced their tangos and watched girls shiver in the appropriate clothes for the Côte d’Azur”. They also went to “the cheap ballets of the Casino on the jetée” and dined on salade niçoise. Venturing as far as Menton, they ordered a bouillabaisse “in an aquarium-like pavilion by the sea across from the Hotel Victoria”. By the time Tender is the Night was published in 1934, the Fitzgeralds had been back in America for three years. Zelda’s mental health had declined and tragic events would mar their happiness, but the golden glow of those endless summers on the Côte d’Azur remained.

Vintage postcard from the Hôtel Belles Rives

Fortunately, some things never change. Take, for instance, Fitzgerald’s rhapsodic description of the shimmering Mediterranean, published in 1924, in The Saturday Evening Post: “the fairy blue of Maxfield Parrish’s pictures: blue like blue books, blue oil, blue eyes, and in the shadow of the mountains a green belt of land runs along the coast for a hundred miles and makes a playground for the world. The Riviera!”

The Hôtel Beau Rivage in Nice back in the day

Today, many of the Fitzgeralds’ stomping grounds are still going strong. The Hôtel Belles Rives remains an elegant Art Deco gem, with a superb restaurant, private beach and waterskiing school; in Nice, the Hôtel Beau Rivage is a stylish hotel with a terrific beach restaurant. If you’re feeling flush after a night at the Monte Carlo Casino, head for the Hôtel-du-Cap-Eden-Roc for their signature Bellini cocktail or dine at the terrace Grill Eden-Roc, overlooking the legendary pool carved out of the rock (www.hotel-du-cap- eden-roc.com). At the far corner of La Garoupe beach, the beau monde flocks to La Plage Keller for toes-in-the-sand dining, featuring Mediterranean classics. After lunch, head to Villa Eilenroc, the Belle-Époque home once owned by the Count and Countess Étienne de Beaumont, whose lavish fêtes Scott and Zelda attended.

Don’t miss your chance to dine at La Colombe d’Or

Return to America: In 1929, the Fitzgeralds spent their last summer on the Riviera. When the Stock Market crashed in the autumn of that year, the gaiety was gone. Living in a villa in a less fashionable part of Cannes, the Fitzgeralds now avoided the Hôtel du Cap, a celebrity circus where silk-clad matrons used the pool “only for a short hangover dip”.

By this time, Zelda, who was doggedly working at becoming a ballerina, was showing signs of mental strain, and their cash was running low. Still, that didn’t stop the Fitzgeralds from exploring Nice, staying at the Hôtel Beau Rivage on the seafront, where “they were serving blue twilights at the cafés along the Promenade des Anglais for the price of a porto and we danced their tangos and watched girls shiver in the appropriate clothes for the Côte d’Azur”. They also went to “the cheap ballets of the Casino on the jetée” and dined on salade niçoise. Venturing as far as Menton, they ordered a bouillabaisse “in an aquarium-like pavilion by the sea across from the Hotel Victoria”. By the time Tender is the Night was published in 1934, the Fitzgeralds had been back in America for three years. Zelda’s mental health had declined and tragic events would mar their happiness, but the golden glow of those endless summers on the Côte d’Azur remained.

Vintage postcard from the Hôtel Belles Rives

Fortunately, some things never change. Take, for instance, Fitzgerald’s rhapsodic description of the shimmering Mediterranean, published in 1924, in The Saturday Evening Post: “the fairy blue of Maxfield Parrish’s pictures: blue like blue books, blue oil, blue eyes, and in the shadow of the mountains a green belt of land runs along the coast for a hundred miles and makes a playground for the world. The Riviera!”

The Hôtel Beau Rivage in Nice back in the day

Today, many of the Fitzgeralds’ stomping grounds are still going strong. The Hôtel Belles Rives remains an elegant Art Deco gem, with a superb restaurant, private beach and waterskiing school; in Nice, the Hôtel Beau Rivage is a stylish hotel with a terrific beach restaurant. If you’re feeling flush after a night at the Monte Carlo Casino, head for the Hôtel-du-Cap-Eden-Roc for their signature Bellini cocktail or dine at the terrace Grill Eden-Roc, overlooking the legendary pool carved out of the rock (www.hotel-du-cap- eden-roc.com). At the far corner of La Garoupe beach, the beau monde flocks to La Plage Keller for toes-in-the-sand dining, featuring Mediterranean classics. After lunch, head to Villa Eilenroc, the Belle-Époque home once owned by the Count and Countess Étienne de Beaumont, whose lavish fêtes Scott and Zelda attended.

No one leaves the Côte d’Azur without dining at La Colombe d’Or in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, surrounded by original works by the great masters. And if you’re a true Fitzgerald fan, rent his former digs Villa Marie in Saint-Raphaël and scribble your own masterpiece.

From France Today magazine

The Belles Rives today

Lead photo credit : Images © John Michel Sordello, Jean-luc Guillet, Hôtel Belles Rives; Alamy

More in Fitzgeralds, French Riviera, Great Gatsby, Hôtel Belles Rives, Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc

From France Today magazine

The Belles Rives today

Lead photo credit : Images © John Michel Sordello, Jean-luc Guillet, Hôtel Belles Rives; Alamy

More in Fitzgeralds, French Riviera, Great Gatsby, Hôtel Belles Rives, Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc

*Frances Scott "Scottie" Fitzgerald was an American writer and journalist and the only child of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald. She worked for The Washington Post, The New Yorker, The Northern Virginia Sun, and others, and was a prominent member of the Democratic Party.

Labels: France Today, Jazz Age, The Great Gatsby